The Cypress Freeway was just one of the urban developments that struck a fatal blow to an already embattled West Oakland.

The Cypress Freeway was just one of the urban developments that struck a fatal blow to an already embattled West Oakland.

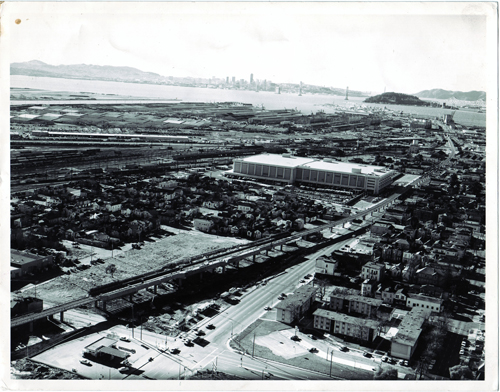

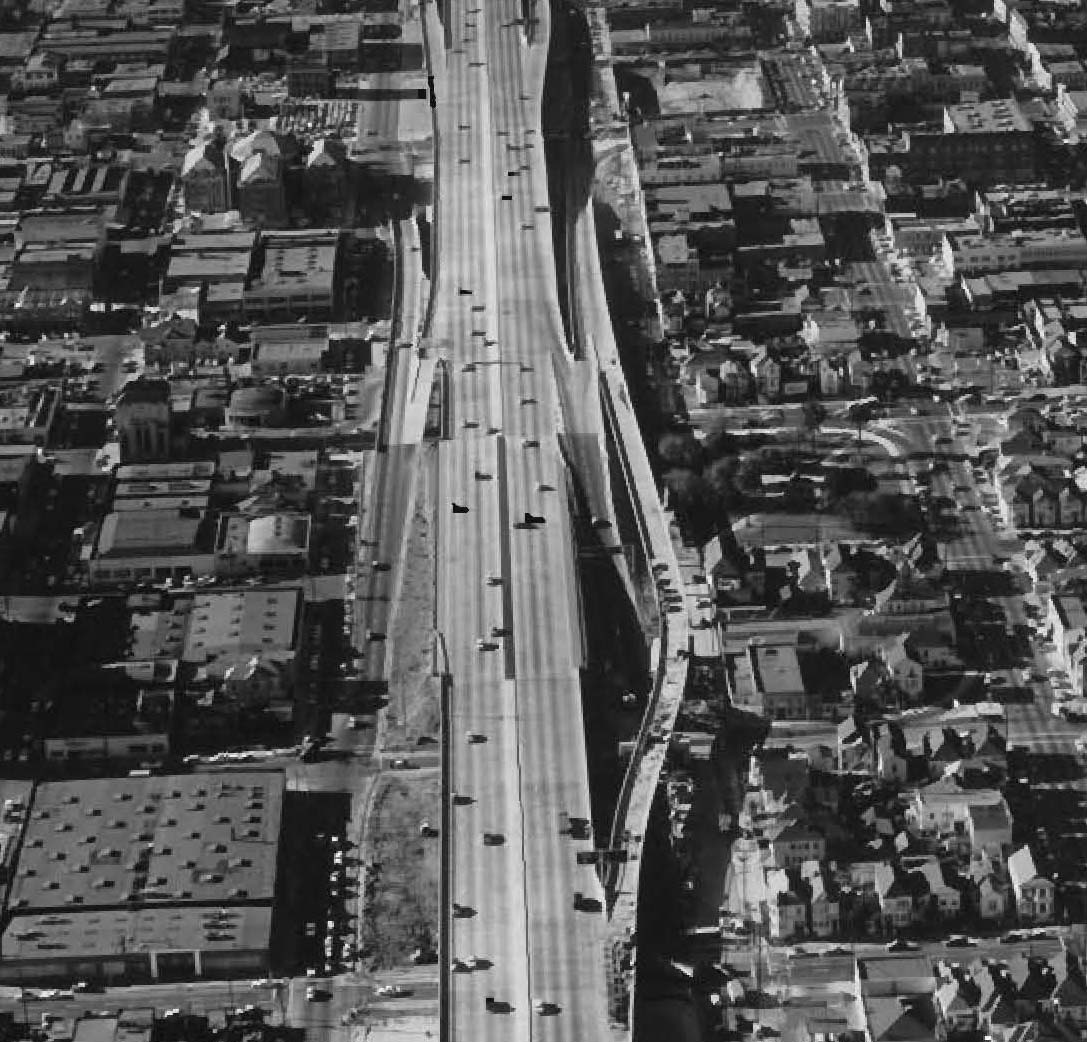

Built in the 1950’s, the construction of the freeway effectively severed West Oakland from the downtown and from Oakland’s more affluent communities. By the time the freeway arrived, West Oakland was already facing economic hardship. During WWII, people came to Oakland from all over the United States to find jobs in Oakland’s shipyards and transit stations. Once the war ended, the boom began to bust.

In order to build the freeway, officials uprooted 600 families and dozens of businesses that stood in the way of construction. The noise and smell from the freeway changed the face of the neighborhood. Some studies showed that residents of West Oakland began to develop a higher incidence of asthma and some cancers than their counterparts in other areas of the city.

Remaining businesses could not survive, and many of them closed. Some West Oakland residents saw the Cypress onslaught as the beginning of the end.

In 1989, the Cypress Freeway collapsed during the Loma Prieta earthquake. The freeway collapse was a devastating event that killed 41 people and shocked the San Francisco Bay Area. When Caltrans planned to rebuild the freeway in the same location, West Oakland activists, under the banner of the Citizens Emergency Relief Team (CERT), proposed a different route for the freeway, one that would minimize impact on West Oakland. CERT boasted an influential local membership, including a BART director, a former mayor of Oakland, and a Port of Oakland CEO.

Over time, CERT and other community groups were able to sensitize Caltrans to some of the neighborhood’s concerns. One area of West Oakland, however, remained outside of both Caltrans’ and CERT’s attention. Although the new route for the freeway was a vast improvement, it still bisected a residential area commonly known as “Lower Bottom.” The residents of that area filed a lawsuit against Caltrans in 1993 charging that the freeway was responsible for excessive noise and pollutants that endangered the community’s health. Though this original claim was settled, more litigation followed when toxic chemicals were discovered under the demolished Cypress pillars.

Caltrans mistakenly believed that CERT represented all of West Oakland. The people of “Lower Bottom” made themselves known to Caltrans but ultimately the new Cypress structure was rebuilt along the new route as planned. With the cooperation of West Oakland businesspeople and city officials, Caltrans renamed the street originally covered by the Cypress Freeway; Mandela Parkway. In 2005 Caltrans completed construction of bicycle paths, walkways, and green areas along the parkway.

The construction of a massive postal distribution facility, along with a freeway and elevated train, ushered in a new era for West Oakland in the 1960s. With its parking and storage lots, the postal facility took up 12 square blocks and contributed to increased pollution in an area already plagued with health problems. When it was built on 7th Street from Wood to Peralta, it displaced every structure on the street’s south side.

The construction of a massive postal distribution facility, along with a freeway and elevated train, ushered in a new era for West Oakland in the 1960s. With its parking and storage lots, the postal facility took up 12 square blocks and contributed to increased pollution in an area already plagued with health problems. When it was built on 7th Street from Wood to Peralta, it displaced every structure on the street’s south side.