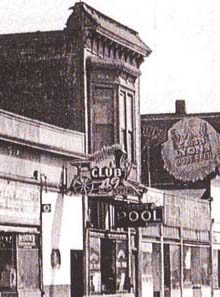

The Stag Pool Hall was downstairs from the offices of C.L. Dellums, West Coast vice president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

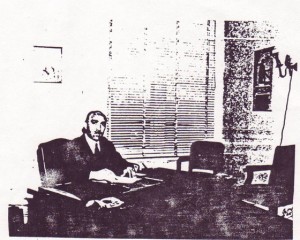

The outspoken Dellums was fired by the Pullman Company shortly after joining the Brotherhood, a union formed to organize railway porters in the company’s employ. When the management of Pullman fired Dellums they told him that by employing him they had provided him with transportation across the country to spread, “Bolshevik propaganda.”

To make ends meet, Dellums opened a pool hall below his union offices.His brother, Verney Dellums, a longshoreman, managed the pool hall. Dellum’s nephew, Ron (Oakland’s current mayor), recalls visiting his uncle at the office. He remembers C.L. wearing a Homburg hat and well-shined shoes.

Stag Pool Hall was at the center of 7th Street social life. Dellums welcomed local and national visitors, including entertainer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, a big star in New York City’s Cotton Club. A counter at the front of the hall sold cigars, cigarettes and candy. Visitors could get a drink from the soda machine, or have their shoes shined in one of the three chairs that lined the far wall.

Like many similar institutions at that time, The Stag was a “man’s world” that few, if any, women were permitted to enter. Reports about other Brotherhood and labor offices at the time suggest that Dellums probably entertained a fraternal crowd; smoking and playing cards, as well as discussing the business and politics of the day.

Marva Dellums, C.L.’s only daughter, remembers, “My father never let me in the pool hall. It was not a place for me. He didn’t want us to hear the cursing and see the smoking. Women weren’t allowed. Not to exclude women but because the men were very protective of the women. It was a place for men. That’s why it was called ‘Stag’.”

Dellums’ union business, however, was reserved for his office above the pool hall, and each of the establishments had separate entrances.

The Stag Pool Hall was not simply a recreation hall. It drew members of 7th Street’s political life to its door. Many passed through for conversation, a good cigar, or a game before heading upstairs to visit C.L. Dellums, a man at the epicenter of the local and national fight for civil rights and economic justice.