Category: People

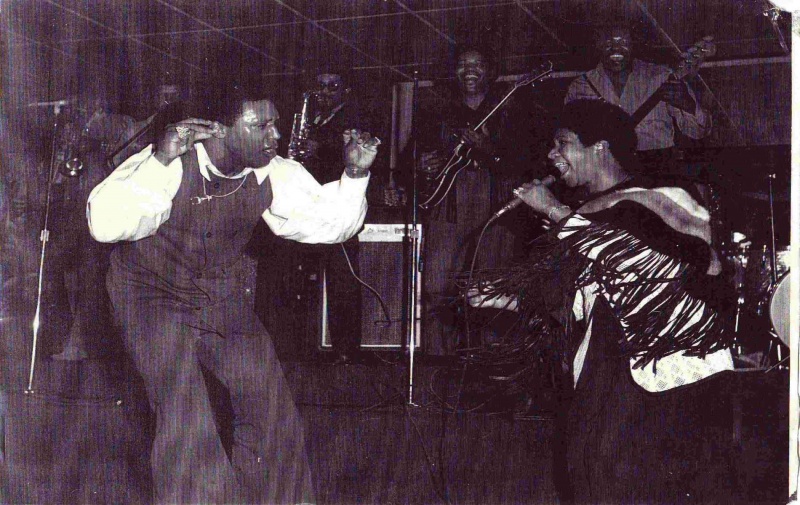

Tom Bowden

From his house on Wood Street, young Tom Bowden watched weary porters and sailors trudge home toward 7th Street’s boarding houses. As a boy he shined shoes for a nickel and later racked pins at the local bowling alley. As he got older, Bowden didn’t just play music on 7th Street. He knew the place; watched the people; understood how his little corner of 7th Street worked. He is often referred to as “The Mayor of Wood Street.”

From his house on Wood Street, young Tom Bowden watched weary porters and sailors trudge home toward 7th Street’s boarding houses. As a boy he shined shoes for a nickel and later racked pins at the local bowling alley. As he got older, Bowden didn’t just play music on 7th Street. He knew the place; watched the people; understood how his little corner of 7th Street worked. He is often referred to as “The Mayor of Wood Street.”

Born into a musical family, Bowden began his career at 7th Street’s Lincoln Theater, singing in talent shows when he was just a kid. When he wasn’t singing, he was fighting, and ran afoul of the law for cracking someone’s jaw. He earned the nickname, “Terrible” Tom Bowden. Bowden claims the name stuck because he was a fearsome boxer.

Bowden soon found his voice in the “doo-wop” style of music on 7th Street, and liked to harmonize with friends. He performed locally at Esther’s Orbit Room and by the 1960’s he was singing with top musicians at popular clubs throughout California. Later he moved on to the Los Angeles music scene and was the first black musician to play at L.A.’s Apartment Club.

In his lifetime, Bowden shared the stage with luminaries like Etta James, Aretha Franklin, Richard Pryor and Ray Charles. He has been described as the only person alive who can sing like the late Otis Redding. He has been praised for his energy and his soulful voice.

Bowden recalls the 7th Street of the past as both a rough neighborhood and a safe close-knit community where neighbors didn’t have to lock their doors. He describes it as “diverse,” where many ethnicities lived together and looked out for one another. His description aptly illustrates the extremes of the once-thriving neighborhood, with its famous musicians, shopkeepers, hustlers, preachers, schoolchildren and dreamers. All were part of Tom Bowden’s world; the world of blues-infused 7th Street.

Now 69 years old, Bowden still lives on Wood Street. Dedicated to West Oakland, Bowden is involved in community projects to help local youth, and still performs at jazz and blues festivals.

Lowell Fulson

Lowell Fulson was born on a Choctaw Indian Reservation in Oklahoma in 1921. But it was on Oakland’s 7th Street that his musical career began.

Lowell Fulson was born on a Choctaw Indian Reservation in Oklahoma in 1921. But it was on Oakland’s 7th Street that his musical career began.

Conscripted into the army and stationed in West Oakland, Fulson occasionally played his guitar on street corners and at house parties. When local record producer Bob Geddins met Fulson, he told him, “If you ever come back through this way, I’ll record ya.”

One day, while visiting friends in the area, Fulson walked into Geddins’ one-man record-press shop on 7th Street. Fulson, who was 25-years-old, grabbed a guitar off the wall and played so well that Geddins signed him to a deal and paid him $100 cash. Geddins pressed Fulson’s first 78 rpm records and sold them from the trunk of his car. Fulson’s sound evoked rural Texas, and his first recorded tune, “Three O’Clock Blues,” was destined to become a B.B. King staple.

From that fateful day in Oakland, Fulson’s career took off, but he rarely played in West Oakland again. He thought Slim Jenkins’ Place was full of “snotty-nosed people.” Fulson saw Esther’s Orbit Room, across the street from Slim’s, as a welcoming down-home place, but he didn’t play there until 1966.

Instead he was destined for the big-time. He toured his smooth “jump-blues” with Ray Charles, Ike Turner and other jazz, blues and soul greats. Among the musicians who recorded his tunes were Elvis Presley and Otis Redding. He soon sparked interest across the country, and was signed to Chicago’s Checker label. He continued to play in clubs on the West Coast, and was especially partial to clubs in Richmond, California.

According to fellow musician Tom Bowden, Fulson was known for his big white guitar, a Gibson 3335 that had three pick-ups.

Fulson was able to write songs that responded to the times. If soul music was the order of the day, he could infuse his sound with soul. If a song required a jazz edge, he could accommodate. He was able to mix different styles to satisfy a range of listeners. In 1954, he recorded with Kent Records under the name Lowell Fulsom. His career didn’t slow down until the late 1960s when rock and roll dominated the music scene, though Fulson continued to perform in clubs and at festivals well into the 1990s.

Though he strayed far from 7th Street, Fulson could not deny its influence. Fulson says it was Bob Geddins who, aside from giving him his first hit, taught him how to phrase the blues, telling him to “…hold that wind in there, boy, before you change that note.” Fulson died in Long Beach, California in 1999.

Saunders King

Saunders King was a blues and jazz giant who began performing on 7th Street as a teenager. His father, the Reverend Judge King, was pastor at the Christ Sanctified Holy Church on 7th Street, where the young King sang in the gospel choir.

King grew up to become one of the most famous musicians to come from West Oakland. On 7th Street, he was part of the house band at Slim Jenkins’ Place, but his fame soon swelled beyond the confines of the neighborhood where he was raised.

In the 1930s, he debuted at a downtown Oakland club called Sweet’s Ballroom, sang on the radio with a group called The Southern Harmony Four, and became a staff artist for NBC Radio. He created a new kind of jazz, and many tried to emulate it

King moved from Oakland to San Francisco in 1938 where he played many popular clubs. In 1942, his album “S.K. Blues” was the first Bay Area blues record to become a hit. Recorded with an electric blues guitar, it was innovative; S.K. Blues was the perfect song for blues “shouters” like Jimmy Witherspoon and Big Joe Turner, who used the power of their booming voices to give their music a special resonance.

King did not tolerate segregation in the clubs where he played. He once threatened to walk out of a club when the owners pulled a rope down the center of the dance floor to separate whites from blacks. Racism was unacceptable to him; those close to him say his music was born of this deep sense of injustice. One of his daughters described him as a man of few words who only spoke when he had something important to say.

He sang with a smooth, clear voice and played guitar, ukulele and banjo. He recorded for top labels like Decca and Aladdin and was considered one of the great electric guitarists. His talents were huge, but so were his demons. A jazz musician who played with him in San Francisco said that he was always in trouble with heroin; he served time in prison on drug charges. He also experienced personal tragedy when his wife committed suicide in 1942. His problems too often eclipsed his remarkable talent.

King’s stability seemed to improve after he married second wife Jo Frances and had two children. He put his troubles behind him when he retired from music in 1961 and returned to Oakland, the scene of his gospel roots where he joined a church and began singing and playing for the congregation. He made a brief comeback in 1979, working with his son-in-law at the time, Carlos Santana, on his album “Oneness.”

In his life and music, Saunders King reflected of the vibrant but sometimes troubled nature of his native 7th Street. He died in 2000, at the age of 91.

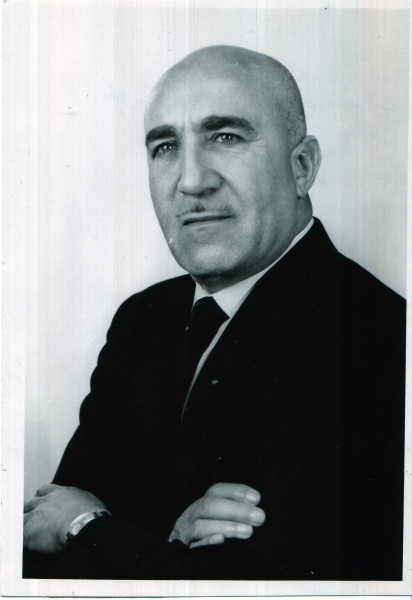

C.L. Dellums

Before he helped organize the nation’s first African American union, C.L. Dellums had dreams of becoming a lawyer. Born in Corsicana, Texas in 1900, Dellums moved to Oakland in the 1920s but found prejudice as alive and well in California as it was in Texas. Discovering that few good jobs existed for blacks, Dellums found work as a railway porter with the Pullman Company. At the time, the company was the premiere owner and operator of railway sleeping cars, a mode of transportation that was sweeping the nation. Dellums took the job but remained committed to his dreams. He read voraciously, and held the written and spoken word in high esteem. People who knew Dellums say that he could have easily been mistaken for a Harvard graduate.

Before he helped organize the nation’s first African American union, C.L. Dellums had dreams of becoming a lawyer. Born in Corsicana, Texas in 1900, Dellums moved to Oakland in the 1920s but found prejudice as alive and well in California as it was in Texas. Discovering that few good jobs existed for blacks, Dellums found work as a railway porter with the Pullman Company. At the time, the company was the premiere owner and operator of railway sleeping cars, a mode of transportation that was sweeping the nation. Dellums took the job but remained committed to his dreams. He read voraciously, and held the written and spoken word in high esteem. People who knew Dellums say that he could have easily been mistaken for a Harvard graduate.

Dellums worked for $2 a day plus tips and owned a billiard parlor on 7th Street to supplement his income. The company expected railroad porters to work 400 hours, or travel 11,000 miles per month, to receive full pay. Porters received no overtime and had to pay for their own uniforms and supplies.

To improve their rights, porters had attempted to organize many times without success. As soon as Dellums (along with and A. Philip Randolph) took up that cause, the Pullman Company fired him. The dismissal did not prevent Dellums from becoming a key player in the porters’ struggles. In 1929, Dellums became the union’s West Coast vice president.

At least 500 workers were fired by the Pullman Company for union activity. Because of this intimidation, it took 12 years for the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters to represent the Pullman porters and gain widespread recognition.

But Dellums didn’t reserve his activism for labor rights alone. He always recognized the fight to organize the Brotherhood as part of a larger one for racial equality. In 1948, Dellums became regional chair of the NAACP, organized civil rights marches, and was appointed to California’s first Fair Employment Practice Commission in 1959.

In 1968, he became President of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. By this time, train travel was in decline, and the Brotherhood was forced to merge with a larger union.

Dellums’ life on 7th Street was as colorful and as passionate as his politics. His billiard parlor was the center of social life. He had visitors from across the country, including entertainer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, a big star in New York’s Cotton Club.

Dellums wore a Homburg hat, smoked a pipe, and his shoes were always shined to a sparkle. While working with the Brotherhood, he took up with an activist named “Dad” Morris, whom Dellums called, “a two-fisted vulgar old man who was quite a scrapper,” and vowed to spread his spirit across the nation.

To his friends, associates, and to his own nephew, Ron Dellums, who became Oakland’s mayor in 2006 after serving as a U.S. Congressman for 27 years, C.L. Dellums was “larger than life.” He died in Oakland in 1989 at the age of 89.